Lecturer in Planetary Science at The Open University (OU):

On 28 February 2021, for the first time in 30 years, a meteorite fell in the UK and was later recovered by scientists. Today, there’s an international effort to study this space rock and learn more about its place in the early solar system.

This meteorite is named after Winchcombe, the town in Gloucestershire where several fragments were recovered – including a piece that landed on the driveway of a family home.

The meteorite formed 4.5 billion years ago in the distant outer solar system, beyond the orbit of Jupiter. We refer to such objects as primitive because they contain some of the earliest solid material to form in our cosmic neighbourhood, offering insights into a time when our solar system was in its infancy.

Over time, much of this solid material merged to form larger objects, which eventually led to the emergence of planets. Some of the early building blocks that avoided being consumed in this process of planetary assembly are present today as asteroids or even smaller objects. The Winchcombe meteorite is just such a celestial body.

Some of these free-roaming planetary building blocks may have been responsible for delivering water to the early Earth. Therefore, Winchcombe can provide a glimpse into the activity of water on solid bodies in the ancient solar system.

Path through space

Winchcombe is a rare type of meteorite known as a CM chondrite. These meteorites are characterised by high concentrations of water and organic matter (molecules with chains of carbon atoms), both of which are essential ingredients for the emergence of life.

We know the path through space that the Winchcombe object took – its orbit – before it fell to Earth. It is one of only five primitive, water-bearing chondrites for which scientists have this information. Knowing its orbit means we can pinpoint where in the solar system it came from.

The meteorite appeared as a yellow-green fireball over Gloucestershire.

The pieces of this meteorite were recovered very rapidly – within 12 hours of arriving on Earth. This means there was little time for water from Earth’s atmosphere to react with and contaminate the meteorite. Taken together with the meteorite’s rarity, primitive characteristics and distant origin, its swift recovery makes the object an ideal candidate for studying the role of asteroids in the early solar system.

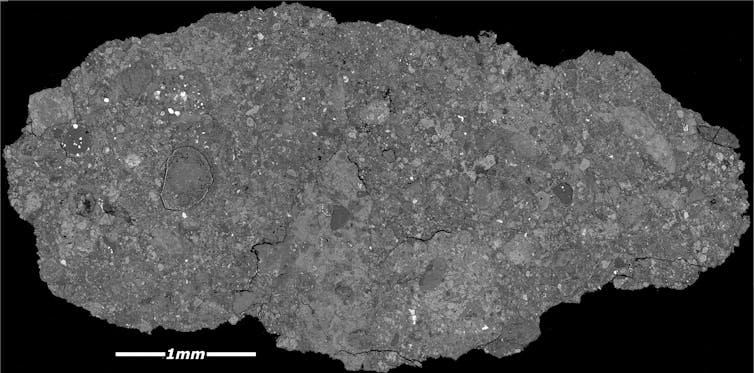

The meteorite was probably once part of a larger asteroid. But looking at pieces of the Winchcombe object under the microscope, it quickly became clear that it is not one rock but many –- a complex mix of fragments loosely held together. This structure is the result of collisions between larger asteroids in space.

The debris field created by the collision subsequently merged to form a new population of smaller second-generation asteroids referred to as rubble-pile objects because of their loose, blocky configuration. Winchcombe came from one of these rubble-pile bodies – fragmented remains of the diverse rocky objects that existed in the age before planets.

Space mud

Each rock fragment that makes up the Winchcombe meteorite records a distinct history, revealing, for example, differences in the amount of water it interacted with, and implying that the parent asteroid had a complex structure.

These observations point to either variable amounts of water on that parent body, which condensed as ice as the asteroid grew, or the uneven flow of water through the asteroid. When space rocks come into contact with liquid water they begin to change, forming an unusual form of dark black, fine-grained “space mud”.

Researchers from across the world jump at the chance to study these minerals because they hold, inside their crystal structure, molecules of

the original water that flowed on these asteroids.

The space rock contains some of the very earliest material to form in the solar system. Credit Mira Ihasz SpireGlobal

A group of scientists accurately measured the different isotopes (or chemical forms) of the hydrogen present in Winchcombe. Along with oxygen, hydrogen is one of the two chemical elements in water. The scientists’ findings demonstrated that water contained within the meteorite is very similar to the water on Earth.

This strengthens a theory that asteroids played a critical role in delivering water to the early Earth and thereby generating the oceans we see today.

Catastrophic collision

At some point, chemical reactions between water and rock were halted by the catastrophic collision with another asteroid. This event shattered the meteorite’s parent body. Most of the rock fragments in the Winchcombe meteorite are very small, less than 1mm in size. This pattern of small pieces is evidence of the high-energy collision but also the signature of a weak asteroid.

As our understanding of planetary building blocks grows, we are increasingly recognising that the types of planetary bodies represented by the Winchcombe meteorite no longer exist in their original form.

The fragmented nature of the Winchcombe meteorite was visible with a powerful microscope. Credit Martin Suttle

Most, if not all, small asteroids (those measuring less than 10km in diameter) are likely to be rubble-pile bodies. Winchcombe is a relic from that time and a testament to the fate of most asteroids. We can summarise their history in a few simple words: hot and wet, then smashed to rubble.

Studying Winchcombe has also helped us to understand how these types of meteorites break-up in the atmosphere and, therefore, why they are rarely found as large rocks.

Research on Winchcombe continues and there are many more science questions that we hope to answer. One particularly interesting study relates to the type and amount of organic matter within Winchcombe and whether organic matter delivered by meteorites played a role in the supply of nutrients – food, essentially – for the emerging life on Earth.![]()

Martin D. Suttle, Lecturer in Planetary Science, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.