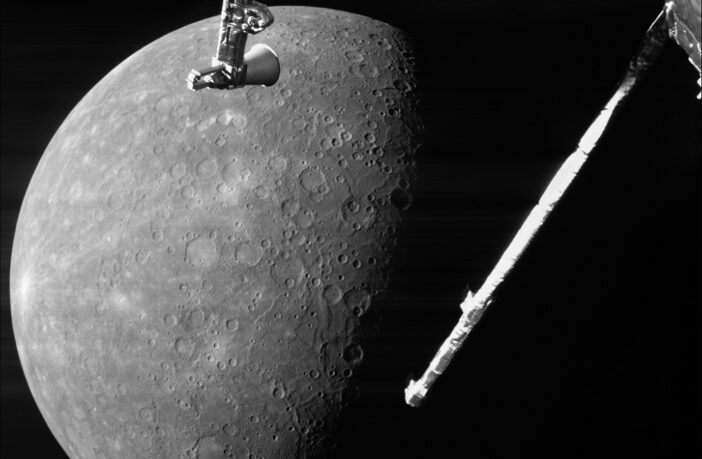

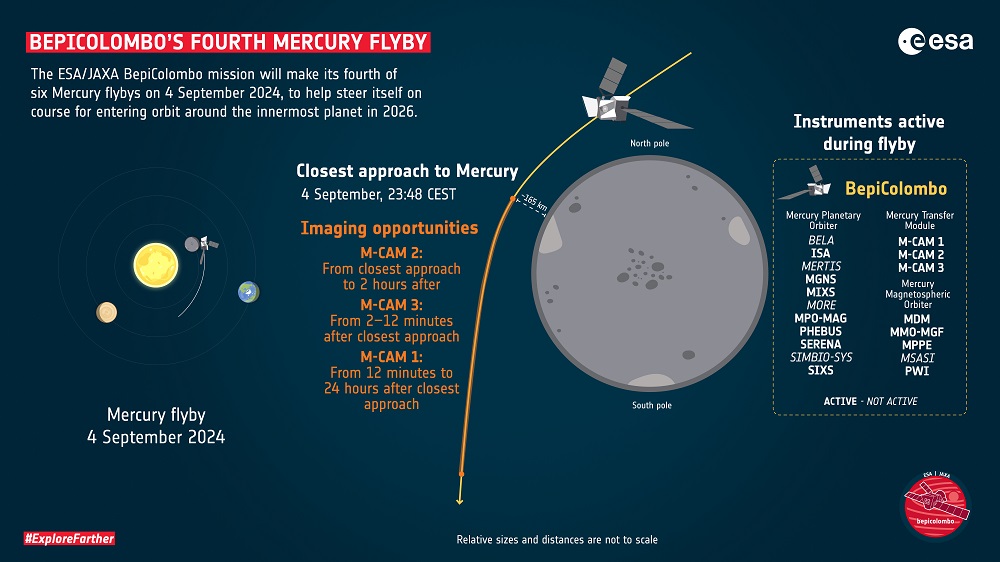

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission has successfully completed its fourth of six gravity assist flybys at Mercury overnight on 4/5 September, capturing images that include two special impact craters as it uses the planet’s gravity to steer itself on course to enter orbit around Mercury in November 2026.

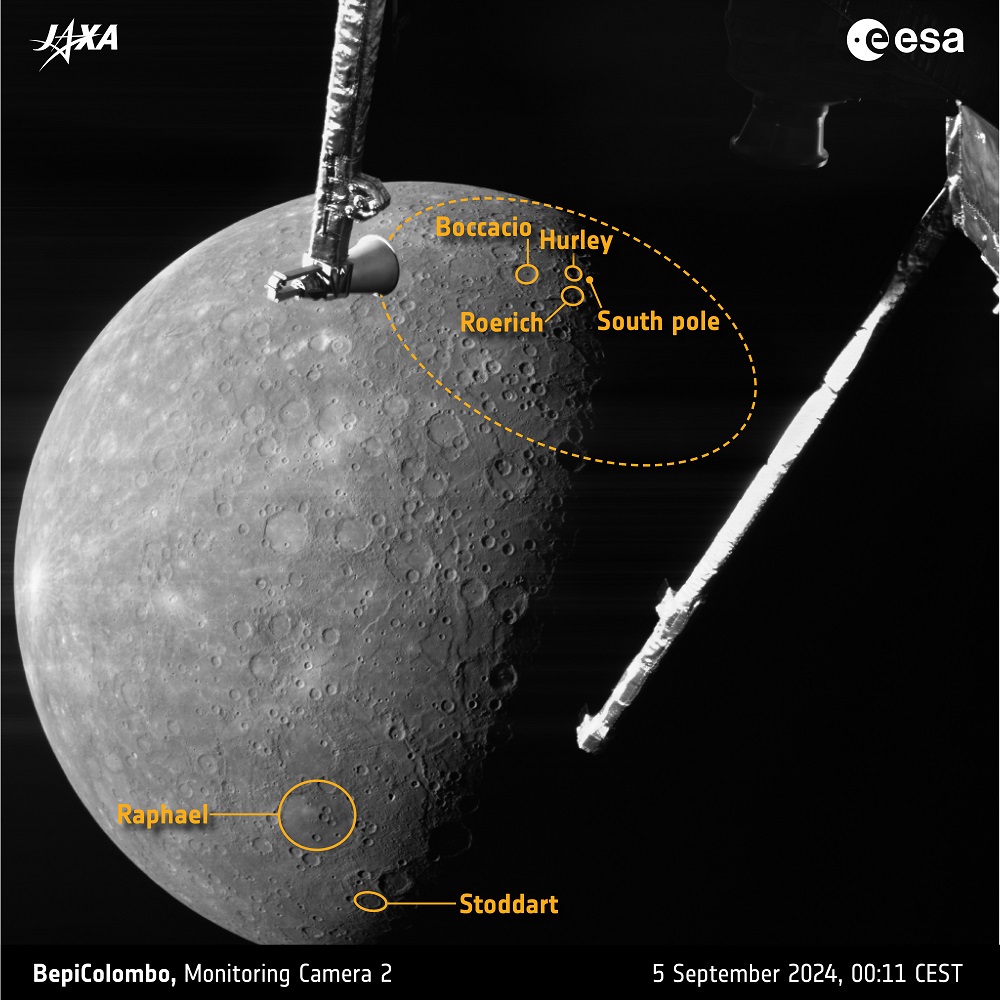

The closest approach took place at 22:48 BST (23:48 CEST) on 4 September 2024, with BepiColombo passing within around 165 km above the planet’s surface. For the first time, the spacecraft had a clear view of Mercury’s south pole.

Images from BepiColombo’s three monitoring cameras arrived back on Earth during the morning of 5 Sept, providing a unique view of Mercury’s surface from three different angles. BepiColombo approached Mercury from the ‘nightside’ of the planet, with Mercury’s cratered surface becoming increasingly lit up by the Sun as the spacecraft flew by.

BepiColombo says goodbye to Mercury for the fourth time. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM

Experts from The Open University (OU) are working as part of the BepiColombo M-CAM imaging team, including David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences at the OU and a member of the BepiColombo M-CAM imaging team, who commented:

“It was worth getting up before 4am for this. The detail of small landscape feature in the images is better than I hoped for. It is making me impatient for the real science when we get into orbit two years from now.”

Mercury lays bare its Four Seasons

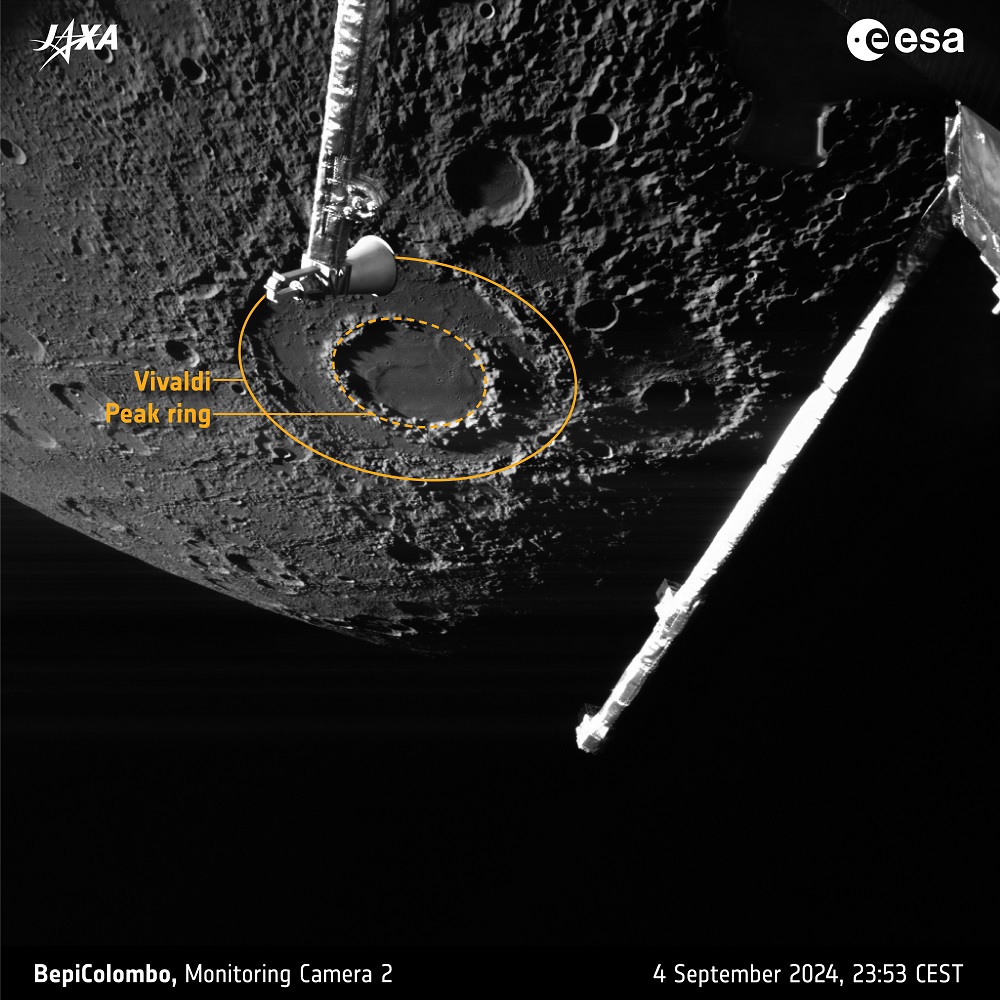

Four minutes after closest approach, a large ‘peak ring basin’ came into BepiColombo’s view. These mysterious craters – created by powerful asteroid or comet impacts and measuring about 130–330 km across – are called peak rings basins after the inner ring of peaks on an otherwise flattish floor.

This large crater is Vivaldi, after the famous Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741). It measures 210 km across, and because BepiColombo saw it so close to the sunrise line, its landscape is beautifully emphasised by shadow. There is a visible gap in the ring of peaks, where more recent lava flows have entered and flooded the crater.

Mercury reveals its Four Seasons. Credit: Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM

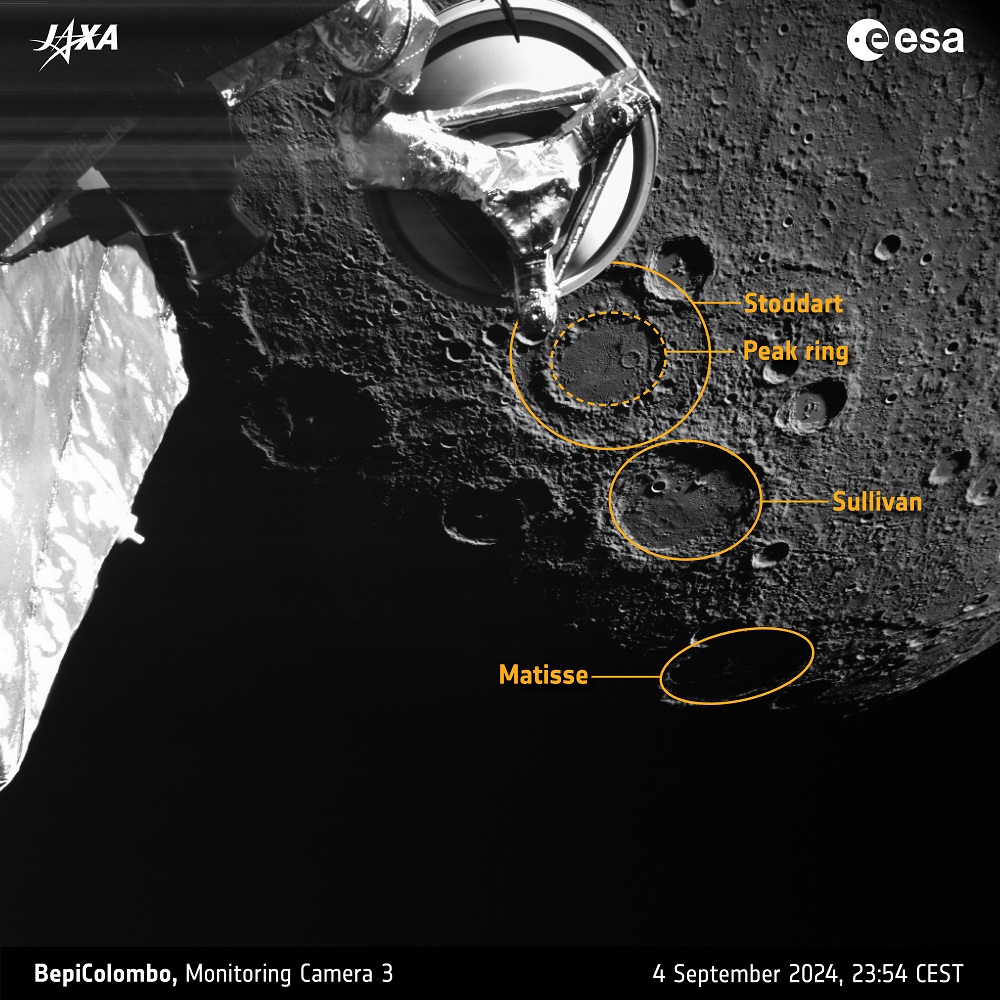

First sight of crater newly named after New Zealand artist

Just a couple of minutes later, another special peak ring basin came into view. This one measures 155 km across.

“When we were planning for this flyby, we saw that this crater would be visible and decided it would be worth naming due to its potential interest for BepiColombo scientists in the future,” explains David.

BepiColombo captures newly named Stoddart crater. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM

Following a request from the M-CAM team, the ancient crater was recently assigned the name Stoddart by the International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature after Margaret Olrog Stoddart (1865–1934), an artist from New Zealand known for her flower paintings.

“Mercury’s peak ring basins are fascinating because many aspects of how they formed are currently still a mystery. The rings of peaks are presumed to have resulted from some kind of rebound process during the impact, but the depths from which they were uplifted are still unclear,” continues David, “Mercury is ‘Lord of the Peak Rings’”.

Many of Mercury’s peak ring basins have been flooded by volcanic lava flows long after the original impact. This has happened inside both Vivaldi and Stoddart. Inside Stoddart, the trace of a 16-km-wide crater that must have formed on the original floor is clearly visible through a covering of more recent lava flows.

Peak ring basins are among the high-priority targets for study by BepiColombo once it gets into orbit around Mercury and is able to deploy its full suite of scientific instruments.

A taste of Mercury science

The snapshots seen during this flyby are among BepiColombo’s best so far – taken from the closest distance yet, with Mercury’s surface well-lit by the Sun. They reveal a surface with clear signs of 4.6 billion years of bombardment by asteroids and comets, hinting at the planet’s place in the wider Solar System evolution.

BepiColombo’s closest approach to Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM

It’s worth remembering that these images are a bonus: the M-CAMs were not designed to photograph Mercury but the spacecraft itself, especially during the challenging period just after launch. They provide black-and-white 1024×1024 pixel snapshots. BepiColombo’s main science camera is shielded during the journey to Mercury, but it is expected to take much higher-resolution images after arrival in orbit.

In 2027, the main science phase of the mission will begin. The spacecraft’s suite of science instruments will reveal the invisible about the Solar System’s most mysterious planet, to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its host star.

But the work has already begun, with most of the instruments switched on during this flyby, measuring the magnetic, plasma and particle environment around the spacecraft, from locations that will not be accessible when BepiColombo is actually in orbit around Mercury.

BepiColombo comprises two science orbiters that will circle Mercury – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. The two are carried together to the mysterious planet by the Mercury Transfer Module. Even though the three parts are currently in ‘stacked’ cruise configuration, meaning many instruments cannot be fully operated, they can still get glimpses of science and enable instrument teams to check that their instruments are working well ahead of the main mission.

BepiColombo’s fourth Mercury flyby. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM

“BepiColombo is only the third space mission to visit Mercury, making it the least-explored planet in the inner Solar System, partly because it is so difficult to get to,” says Jack Wright, Visiting Research Fellow at the OU and ESA, Planetary Scientist, and M-CAM imaging team coordinator.

“It is a world of extremes and contradictions, so I dubbed it the ‘Problem Child of the Solar System’ in the past. The images and science data collected during the flybys offer a tantalising prelude to BepiColombo’s orbital phase, where it will help to solve Mercury’s outstanding mysteries.”

OU research student, Annie Lennox, is in the final stages of mapping the south polar region of Mercury, much of which appears in the global image from this flyby. Annie commented:

“The images released so far are BepiColombo’ s first ever of Mercury’s south polar region, an area close to my heart. For the last three years I have been creating geological maps of Mercury’s south polar quadrangle, an area known as the Bach quadrangle or H15. As can be seen in these pictures, the area is covered in tectonic scarps and impact craters; some of which are host to features I’ve been researching called lobate ejecta, and others in permanent shadow containing water ice. It’s a fascinating area and getting a taste of the higher resolution images that are to come is most exciting.”

What’s next?

This fourth Mercury flyby has lined BepiColombo up for a fifth and sixth flyby of the planet on 1 December 2024 and 8 January 2025. Each is bringing the spacecraft more in tune with the orbit of Mercury around the Sun.

The BepiColombo flight control team will remain extra busy until the end of the sixth flyby, after which they return to normal cruise operations for almost two years, until BepiColombo enters orbit around Mercury in November 2026.