Dr Gemma Briggs, an expert in distracted driving, writes about education campaigns which aim to make drivers aware of road safety issues:

This week is Road Safety Week, organised by the charity, Brake. The week is aimed at raising awareness and educating all road users about aspects of road safety. Across the UK, people will be raising awareness in a range of activities from school children wearing brightly coloured clothing to explain how cyclists can best be seen on the roads, to workplace training promoting safer driving practice. This annual event takes great, effective steps in making our roads safer and it does so largely through educating the general public.

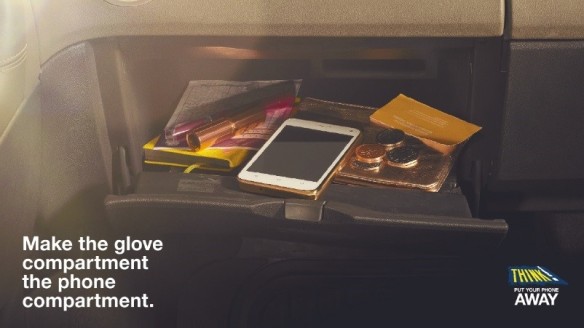

It may appear obvious that teaching the public about specific road safety issues could save lives. Indeed, alongside Brake’s work, successful campaigns run by Think! have been used to educate the public on key road safety messages. These campaigns attempt to deter drivers from ignoring laws relating to driver safety, such as speeding, drink driving, or using a phone while driving. Campaigns are used to support and explain the legislation they apply to. For example, the recent Think! campaign on distracted driving implored the public to ‘make the glove compartment the phone compartment’, with the advert ending with a reminder that those caught using their phone while driving face a £200 fine and 6 penalty points.

These kind of campaigns appear to be relatively successful in terms of changing public attitudes. In the latest British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS 35, 2017), 70% of drivers agreed that using a hand-held phone while driving was unacceptable, demonstrating a marked shift in attitudes compared with the previous 10 years. While this is a promising change, it is likely that recent increases to fines and penalty points of drivers caught using phones contributed to this shift. Nevertheless, there is of course a difference between what an individual says is unacceptable and what they actually choose to do while driving.

Statistics show that a high number of road accidents continue to be attributed to driver inattention (Atchley, Tran & Salehinejad, 2017). One research project (Dingus, Guo, Lee, Antin, Perez, Buchanan-King & Hankey, 2016) which recorded drivers’ behaviour over a three year period found that drivers were engaging in distracting activities for more than half of the time they were driving, which doubled their risk of crashing compared to when they were driving undistracted. The effect on driving varied as a result of the type of distracting behaviour engaged in, such that using a touchscreen, for example, increased the risk of a crash approximately five-fold, while using a hand-held mobile phone was associated with a four-fold increased crash risk.

It’s not just hand-held devices that are problematic though. Decades of research has demonstrated that hands-free phone use is as distracting as hand-held phone use, due to the demands it imposes on a driver’s attention. Phone-using drivers are more likely to miss hazards, even when they occur directly in front of them (Briggs, Hole & Land, 2016); will take significantly longer to react to any hazards they do see, leading to greatly increased stopping distances (Briggs, Hole & Turner, 2018); and are four times more likely to crash than undistracted drivers (Redelmeier & Tibshirani, 1997). While various theoretical explanations have been put forward to explain the cognitive distraction caused by phone use, the negative effects on driving performance have been widely replicated and verified. Why then do safety campaigns only focus on the dangers of hand-held phone use?

The answer is simple: hand-held phone use is illegal, and the Government therefore wish to deter people from this type of offending. Hands-free phone use is not directly legislated against and is, in many areas, promoted as the safe alternative to hand-held phones. Many car manufacturers promote the idea of ‘connected vehicles’ which allow drivers to keep their hands on the wheel and their eyes on the road – a message which ignores research findings demonstrating that hands-free offers no safety benefit to drivers (Ishigami and Klein, 2009). Unless refuted by the advertising standards agency, no rules prevent car manufacturers making such ‘safety’ claims about the technology in their vehicles.

In 2017, when mobile phone legislation was updated, the Government chose to remove the option for first time offenders to attend an educational course aimed at changing behaviour. This was because they felt the option of a course diluted the severity of the offence and considered that increased fines and points would be more of a deterrent than education. This decision came after the tabloid media published articles claiming that the police favoured offering courses over increased fines, and that education courses allowed offenders to ‘dodge bans….rather than being hit with penalty points’. This move ignored the role that education can have in changing behaviour, and preventing further offending, as well as evidence highlighting the effectiveness of the courses that had been offered up to that point. Education courses are also commonly offered across the UK for drivers who have committed speeding offences, and research has shown them to be very effective in terms of altering driver behaviour in the long term, above and beyond penalty points and fines.

By removing the opportunity for educators to explain to offenders why their behaviour was unsafe, the Government has removed a crucial element in the drive to reduce re-offending. The RAC’s response supports this view, suggesting that ‘…concerted action by the Government, police forces, road safety groups and motoring organisations working together..’ is required to address the ‘…handheld phone epidemic that has gripped the UK’. Given the issues of enforcing the current laws, despite some promising technological advancements, it appears that education has a key role to play in changing behaviour. What seems to have been missed in this strategy is an understanding that a balance of approaches to tackle this problem is needed. Namely, campaigns can attempt to deter offending in the first place, the police can enforce the law when necessary, and education can be offered to both prevent re-offending (when offered after enforcement) and to deter others from offending (when proactively offered via campaigns).

Recently, a new Think! campaign – the very imaginative pink kittens film – went further than simply attempting to deter drivers from using their phones with the threat of fines and penalty points. Instead, the ad neatly demonstrated what a driver can miss when looking at their phone, providing a concrete example to the public of why laws are in place. While this campaign was clearly focused on hand-held phone use, it could have gone a lot further to act as a deterrent to all phone use while driving. Instead, while this campaign is a great deterrent for hand-held phone use, it implicitly suggests that the main danger of phone use is not having your eyes on the road and your hands on the wheel (potentially advocating the use of hands-free systems). While these are of course dangers, research has shown that drivers using a hands-free phone can look directly at a hazard yet still fail to see it (Strayer, Drews and Johnston, 2003; Briggs et al. 2016). The key issue, which needs to be represented in safety campaigns, is that a phone-using driver does not have their mind on the road.

I’ve previously asked if the laws on mobile phone use while driving fully reflect scientific knowledge. Until there is a ban on all phone use while driving, the law will fail to adequately reflect research findings. However, that doesn’t negate the responsibility of the Government to make the public aware of this research, via safety campaigns which are informed by scientific findings. These need to be carefully crafted to ensure they reflect current law, to act as a deterrent, yet don’t by implication promote hands-free phone use as a safe activity.

A strategy of both educating offenders, as well as the wider public, could reduce offending and literally save lives. Our current project in collaboration with the Centre for Policing Research and Learning is aimed at addressing these issues, with a view to creating educational resources, informed by current research, which will be freely available to everyone.

This article was originally published on the OU’s criminology blog.

Read more about Dr Gemma Briggs research:

Why hands-free phones aren’t hazard free

Despite the dangers, car firms are still pushing hands-free technology

Seven fails by drivers on hands-free phones

Five things you’re not doing properly when you’re on your phone