The lives of hundreds of thousands of people have been transformed by their study at The Open University, but few can have valued it more than Evelyn Lipmann.

Evelyn, now 94, enrolled for a Humanities degree in the early 1970s to help put behind her the horror of the Nazi concentration camps. Decades later, she credits her OU degree with helping rebuild her self-respect and heal some of the scars left by witnessing terrible suffering. It also, finally, gave her the confidence and strength to tell her story to the Holocaust Educational Trust.

She survived internment in four camps – Teresienstadt, Auschwitz, Bergen Belsen and Salzwedel – before finally being liberated by US forces in 1945.

Today she reflects on her journey, from Vienna to the present day, and how The Open University helped her to regain her confidence.

Evelyn’s Early Years

Evelyn grew up in Vienna, the only child of Fritz and Lily Guttmann. Her childhood and her education were cut short when the Nazis marched into Austria in 1938.

The adoption of the Nuremberg Laws, which banned Jewish children from attending school, effectively imposed a kind of house arrest in the family apartment. But she did what she could to carry on learning.

An Austrian woman who lived nearby, and had visited Ireland, chose to ignore the law and taught Evelyn basic English using AA Milne’s poem Now We Are Six – an act of kindness that would help shape her later life.

She also signed up for evening life drawing classes at the famous Viennese art school, the Kunstgewerbeschule, but she was denounced by another pupil who asked the teacher why he was teaching a Jew. The elderly teacher felt compelled to declare that henceforth no 15-year-old would attend life classes. Evelyn was determined not to give up on art and on Sundays when there were guides giving talks – at immense risk to her safety – she would remove her yellow star and quietly enter the Albertina Print Gallery to gaze at the pictures unnoticed.

Relocation of the Jews

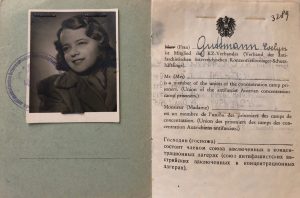

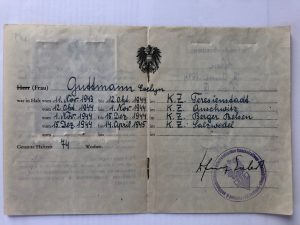

Evelyn Lipmann’s wartime record card

By the early 1940s, even that became impossible. Jews were ordered to move to a specific area of Vienna and she and her mother were made to sew German army caps for 10 hours a day. When the deportations began, the family was sent first to Teresin in Czechoslovakia in 1943 and later transported East to Auschwitz.

Evelyn was interned in four concentration camps

Amazingly, although they lost touch with her father, both Evelyn and her mother survived 18 months in camps in which countless thousands died. Only after the war did they discover that Fritz did not survive, nor did they ever find out how or when he died.

Liberation

Evelyn (centre), working for American Occupation Forces

The smattering of English picked up from her neighbour years before then became key to their post-war life. It secured Evelyn a job in the Property Control Office of the US Occupation Forces. The small salary meant that she could rent a room for her and Lily and allowed them to dream of joining relatives in England.

In 1947, that dream came true. They moved to England and within a year Evelyn met and married her husband Eric and settled in Walton-on-Thames. Two children, Anthony and Katie, followed a few years later.

Through the years of motherhood and school, her own missing education nagged away at Evelyn. And it was The Open University, which enrolled its first students in 1971, which was to help her regain her self-confidence and fulfil her potential.

Evelyn finally completed her education

From the start, the OU was conceived as open to all, regardless of previous educational achievements. Evelyn, who had no education certificates, was enrolled on a foundation course in 1972 and went on to study for her degree over six years.

Three decades after being forced to leave school she was at last able to revel in the joy of learning. The OU taught her how to study and exposed her for the first time to some of the great works – among them Eric Hobsbawm’s Age of Revolution 1789-1848, Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations and George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Evelyn said:

“I had no confidence. None. How could I have confidence when I was treated like dirt?”

Nobody encouraged me to learn. But the fact that I was able to pass exams, write my essays, even though most of the time they were Cs – it gave me confidence. Before, there was nothing to prove I could do anything.

“Lack of education made me feel worthless; education gave me confidence where there was none at all.”

OU allowed Evelyn to revisit her past

It was only when the local paper picked up the remarkable story of an Auschwitz survivor in her 50s having achieved an OU degree that her children began to understand what she had endured.

Anthony said:

“My mother hardly ever talked about her time in the camps. Just after liberation in 1945, she had written a small number of letters to tell relatives she was alive and to search for news of her father. Apart from that, she locked up her memories and threw away the key.

But when recently approached by the Holocaust Educational Trust, she felt the urge to try and tell her story to a wider audience as a witness to such terrible events. Falteringly, this was done in a recorded video interview conducted with Natasha Kaplinsky which is scheduled to be one of many testimonies of survivors and liberators gathered for a new learning centre to be built near Parliament. During the interview my mother spoke of how important the OU had been in re-building her post war life for which she remains to this day eternally grateful, giving her back some modicum of self-worth.”

Evelyn said the roots of the decision to talk about the past lay in her years with the OU.

“The OU made it possible for me to express myself so much more clearly. I never had any counselling after the war and was not able to talk before, whereas I know lots of others were. It was very hard to dig it up; I had to remember everything I had been trying to forget. It is terribly important to me that I speak as an actual person who has been through it. In the end it helped and now I am able to talk about it.”

Evelyn and Anthony were to graduate within a year of each other, he from Oxford and she from the OU. “I know whose was the greater achievement,” said Anthony.

The OU degree certificate, awarded on 12 December 1979, bore the serial number A5832. For Evelyn it marked a significant victory in the long struggle to put behind her a more sinister number, A25466, tattooed on her arm in a Nazi concentration camp.

Main image Copyright: Emma Cattell