Tantalising evidence has been uncovered for a mysterious population of “free-floating” planets, planets that may be alone in deep space, unbound to any host star.

The results include four new discoveries that are consistent with planets of similar masses to Earth, published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

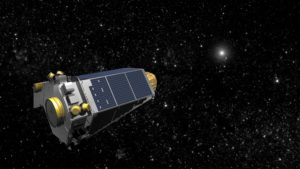

The study, led by Iain McDonald of The Open University (with his former team at University of Manchester) used data obtained in 2016 during the K2 mission phase of NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope.

Signals from planets of similar masses to the Earth

During this two-month campaign, Kepler monitored a crowded field of millions of stars near the centre of our Galaxy every 30 minutes in order to find rare gravitational microlensing events.

The study team found 27 short-duration candidate microlensing signals that varied over timescales of between an hour and 10 days. Many of these had been previously seen in data obtained simultaneously from the ground. However, the four shortest events are new discoveries that are consistent with planets of similar masses to Earth.

The ageing Kepler telescope captured the planets (photo: copyright NASA)

These new events do not show an accompanying longer signal that might be expected from a host star, suggesting that these new events may be free-floating planets.

Planets normally form around a host star, but their orbits can be influenced by the gravitational tug of other, heavier planets and stars in the system. Free-floating planets are probably formed after these heavier bodies “sling-shotted” lighter planets out of orbit, which then end up floating freely through space.

Dr McDonald, now a lecturer in Astrophysics at the OU, said:

“A free-floating planet can be ejected from its orbit around a star at any point in the star’s life, but we think it should be most common when stars form, so learning about free-floating planets tells us a lot about how planetary systems form too. There could potentially be tens or even hundreds of billions of free-floating planets in the Milky Way Galaxy alone, passing quietly unseen been the stars.“

Einstein and microlensing

Predicted by Albert Einstein 85 years ago as a consequence of his General Theory of Relativity, microlensing describes how the light from a background star can be temporarily magnified by the presence of other stars in the foreground. This produces a short burst in brightness that can last from hours to a few days. Roughly one out of every million stars in our Galaxy is visibly affected by microlensing at any given time, but only a few percent of these are expected to be caused by planets.

Kepler was not designed to find planets using microlensing, nor to study the extremely dense star fields of the inner Galaxy. This meant that new data reduction techniques had to be developed to look for signals within the Kepler dataset.

Dr Iain McDonald said:

“These signals are extremely difficult to find. Our observations pointed an elderly, ailing telescope with blurred vision at one the most densely crowded parts of the sky, where there are already thousands of bright stars that vary in brightness, and thousands of asteroids that skim across our field.

“From that cacophony, we try to extract tiny, characteristic brightenings caused by planets, and we only have one chance to see a signal before it’s gone. It’s about as easy as looking for the single blink of a firefly in the middle of a motorway, using only a handheld phone.”

Confirming the existence and nature of free-floating planets will be a major focus for upcoming missions such as the NASA Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, and possibly the ESA Euclid mission, both of which will be optimised to look for microlensing signals.

Co-author Eamonn Kerins of the University of Manchester said:

“Kepler has achieved what it was never designed to do, in providing further tentative evidence for the existence of a population of Earth-mass, free-floating planets.

“Now it passes the baton on to Roman that will be designed to find such signals, signals so elusive that Einstein himself thought that they were unlikely ever to be observed. I am very excited that the upcoming ESA Euclid mission could also join this effort as an additional science activity to its main mission.”

Future observations of these mystery planets will need to wait for the Roman Telescope to be launched, Kepler in the meantime has proved its worth as a pilot study.

(Main image: generic lone planet, copyright NASA)