Locally sourced breeze blocks placed on the sea floor could increase depleted sea urchin populations and support the growth of healthy coral reefs, a new study suggests.

Researchers, led by The Open University (OU) and Operation Wallacea (OpWall), have found that strategically placed artificial reefs in the sea could be used to stimulate population recovery in a keystone species – an organism that maintains an entire ecosystem – thereby helping to restore coral reefs in the Caribbean.

Coral reefs cover less than one per cent of the ocean but they’re home to a quarter of all marine life – that’s more species than rainforests. Animals, including sea urchins, use reefs for shelter, food and laying eggs.

Sea urchins are important to coral reefs because they graze on macroalgae – a type of seaweed found on the reef – and prevent it from smothering the coral.

A disease outbreak in the 1980s decimated urchin populations in the Caribbean, most of which have not fully recovered. Since then, Caribbean reefs have become increasingly dominated by macroalgae, while coral has declined.

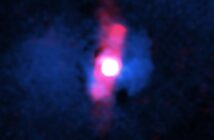

Diadema antillarum, the long-spined sea urchin

This study provides new insights into the importance of a complex habitat structure for the Caribbean sea urchin species, Diadema antillarum.

Dr Max Bodmer, a former student at The Open University, said:

“The findings from our study allow us to tentatively suggest that the strategic placement of artificial reefs could be used to stimulate Diadema population recovery and help to restore reef health to the highly degraded Caribbean.”

A simple, low-cost solution

The researcher team found that habitat complexity is important in determining the distribution and abundance of these keystone grazing urchins. A lack of natural complexity may prevent urchin populations, and therefore reefs, from recovering.

Fortunately, simple, cheap artificial reefs could offer a solution that allows urchins and reefs to recover. For urchins at least, that recovery may be relatively rapid.

Researchers conducted lab and field-based experiments in Honduras to investigate the importance of habitat structure for determining sea urchin population dynamics.

Locally sourced breeze blocks serve as artificial reefs

Findings suggest that Diadema population dynamics and behaviours are controlled by the availability of complex habitats. Using this evidence, the team placed 30 experimental artificial reefs on the degraded reef system of La Ensenada, Tela Bay, in Honduras.

After two years, adult sea urchin densities increased more than threefold around these artificial reefs, and juveniles increased by more than seven times. There was also a promising decline in macroalgae cover, indicating that some of their lost ecosystem function had been restored.

An effective conservation strategy

Dr Bodmer adds:

“Deployment of artificial reefs on a local-scale may establish a positive feedback loop that would reinforce recovery without the need for continual intervention. Restoration of Diadema herbivory would increase coverage of structurally complex corals, which would, in turn, provide more shelter for urchins and stimulate further population increases.”

Dr Philip Wheeler, senior lecturer in ecology at The Open University, said:

“This study shows how important the ecological functions that some species carry out can be for whole ecosystems. Many factors have caused declines in the health of Caribbean reef systems, and a loss of urchin grazing seems to be an important one. This work points to a simple intervention we can make to help restore urchins and their ecological function to degraded reefs.”

Dr Dan Exton, head of research at OpWall, said:

“The fact that we can construct artificial reef structures that have significant ecological benefits from cheap, locally-sourced and widely available materials means that this is a solution that has the potential to be deployed across the Caribbean.”

Dr Pallavi Anand, senior lecturer at The Open University, said:

“The coral reef habitat is likely to be severely impacted by the current climate emergency. Effective conservation strategies such as the one shown in this study, for the Caribbean, are essential if we are to protect and restore coral reef ecosystems on our Blue Planet.”

The joint project between The Open University and OpWall was in collaboration with University College Dublin, Imperial College London, and Tela Marine Research Centre, Honduras.

For more on the research findings, read the paper in Nature Scientific Reports.