“David Attenborough has left more tracks across the broadcasting landscape than any other human being, and his 90th birthday is a good moment to reflect on what makes him special,” says Dr Joe Smith, OU Professor of Environment and Society, who is leading a research project entitled Earth in Vision, exploring environmental change through the BBC archives from 1960 to 2010. In this article he uncovers some of the traits that help assign David Attenborough the title of ‘national treasure’ and looks at what the future holds for environmental TV programmes and presenters…

David Attenborough’s 60-year career has built up an astonishing archive of footage and sound, but also a vast stock of public trust. This has been sparingly deployed, often to the frustration of environmentalists. For decades now broadcasters and commentators have been trying to identify ‘the next David Attenborough’. However, it’s not as if the job has become vacant: in recent years he has been as busy as ever. Nevertheless his birthday prompts us to offer a new and provocative answer to the question. Changes in the media mean that you can be. We all can be. But you will have to sign up to some simple principles that we share below.

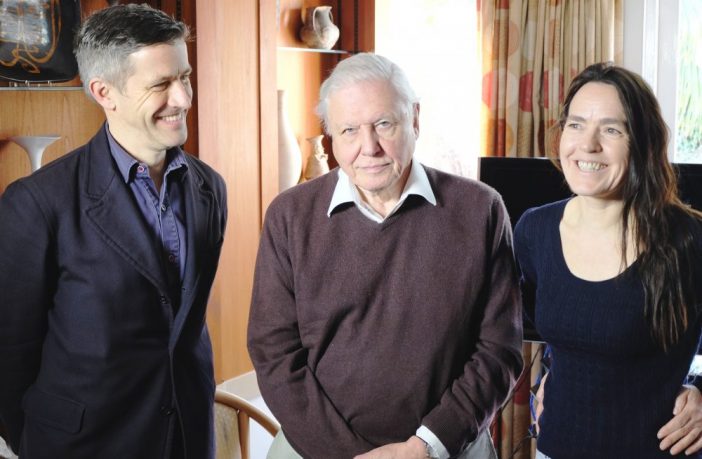

Sir David Attenborough was interviewed as part of the Earth in Vision research project.

Earth in Vision: 100 programmes, 50 years

Our answer to this playful question is derived from work on an Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project Earth in Vision that has seen us working with 100 programmes from across 50 years of BBC environment and natural history programming, and interviewing 30 programme makers and presenters, including the man himself.

When the question is put to David Attenborough he tends to point out there are plenty of other presenters, and viewing figures for the Desmond Morris shows of the past, or for new formats such as the ‘Watch’ programmes (Springwatch etc), with team-based presentation, bear him out.

Secondly, he notes that he was lucky to be in the right place at the right time, and that for most of his career he has not had to compete with such an array of channels and media platforms. Gone are the days when you could literally fit all the big household names in television in your own front room.

‘Living national treasure’

And he adds that natural history film making has long been a big team effort, and that he is primarily the front man who depends on sound and camera crew, specialist advisors, editors, producers and many more. Of course his care in making these points only adds further lustre to the badge of ‘living national treasure’.

David Attenborough comes face to face with an armadillo.

But David Attenborough, and natural history media producers more generally, have long been criticised by environmental researchers and NGOs for their failure to tell the truth about environmental harm. Film makers get excited by a close-in shot of a fascinating behaviour by an engaging mammal, perhaps caught for the first time with great technical virtuosity and determination.

But they might neglect to show that a wider angle on the same scene would show a habitat diminished or threatened by human actions. Attenborough and many of his colleagues have consistently replied that ‘you cannot care for what you don’t know’ and that great storytelling about the natural world can help to build awareness and concern.

Bad box office

Furthermore, channel controllers and commissioners remain convinced that ‘bad environmental news makes for bad box office’. They get and keep their jobs by having strong gut instincts about what audiences want, and they have been almost universally of the view that climate change is a ‘creative challenge’ that generally needs to be ‘smuggled in’ rather than presented head on.

The OU’s Dr Mark Brandon and Sir David Attenborough on location during the filming of Frozen Planet.

There have, however, been some key moments when the boundary between ‘natural history’ and ‘environmental’ programming has been dismantled. In 2000 he fronted State of the Planet which for the first time threaded together and updated a body of his past natural history programming in order to summarise humanity’s environmental impacts. In 2006 he invoked his – and our – responsibility to future generations when explaining to popular newspapers his decision to make a two-part series that sought to summarise the threats, and available actions, related to climate change.

The blockbuster OU/BBC co-production Frozen Planet series that followed found a more natural integration of climate change and other challenges into the main script of what was outwardly a ‘traditional’ blue chip natural history series. But in the case of all of these series Attenborough has been careful to ensure the sound academic footing of the script. In the case of Frozen Planet the OU’s Mark Brandon was the academic advisor, and the climate change two parter drew on experts from three faculties, including me, Mark and climate leadership specialist Stephen Peake.

Another of David Attenborough’s consistent qualities is his technological prescience and commitment to innovation. When he made his very first programmes as presenter, Zoo Quest, he was ordering his own safari suit and heading out with a skeleton crew to film the capture of exotic animals to bring back to London Zoo. Files in the BBC’s paper archives show that he was determined that they be filmed in colour, even though the UK was still years away from colour transmission (an event driven by Attenborough when he held the post of BBC Two Controller). He badgered colleagues until the extra film stock costs were accepted. Those films will now be screened for the first time in colour on BBC television to mark his 90th birthday.

‘Because he tells the truth’

Our recent interviews with other producers and presenters as part of the Earth in Vision project (find out more on the blog) suggest that the natural history community is now far more willing to tell more complex stories – including the sharing of ‘difficult’ news and the posing of direct challenges to audiences. And it is also clear that digital and social media make the notion of ‘audience’ somewhat dated. Most 15-year-old children will be carrying a record and edit suite in their pocket, and have the capacity and opportunity to communicate insights and awareness of change amongst trusted peers. The next phase of our work plans to explore these.

There is no need to wait for the post to become vacant to apply to be the next David Attenborough. Anyone equipped with a smart phone can fill the boots. You just need to be curious and honest, be open to innovation and work hard at your storytelling. Workshops were held to explore what citizens, teachers and learners might want to do with digital broadcast archives. In the course of the workshop we asked what made David Attenborough special. One of the mums present said ‘his voice’ but her 10-year-old simply said ‘because he tells the truth’. Sharing well-told stories about our fascinating but threatened world is a job we should all be taking up.

Find out more:

- Read our ‘happy birthday David Attenborough’ article. His relationship with the OU started back in 1980.

- David Attenborough and The Open University on OpenLearn